“Maybe previous, but never former – once #BDNYC, always #BDNYC!” – Emily Rice

Written By: Stephanie Douglas

The BDNYC group has been around for a while now, and now some of the older members are in positions to provide new opportunities for the current undergrad crowd. Alejandro Núñez and I both joined BDNYC as undergrads: he as a Hunter College student, I as an NSF-funded REU student at the American Museum of Natural History. Then we both chose to do our graduate work at Columbia University – and with the same advisor, Marcel Agüeros. Our group studies rotation and activity in open cluster stars, and we typically receive 10-14 days of time per year on the 2.4m Hiltner telescope at MDM Observatory to take spectra of stars and study their H-alpha emission. This winter, Alejandro and I offered to take along any BDNYC undergrads who were interested in some hands-on observing experience.

MDM is a great place to learn how to observe. It’s a small, privately owned observatory, and it’s relatively easy for members to get lots of time. There’s also no overnight staff – observers are responsible for everything from judging the weather to pointing the telescope to fixing minor problems, in addition to running the instruments to gather their data. Having all that control is a great learning experience — though personally, it makes me *really* appreciate the operators at bigger observatories who let you focus on the data!

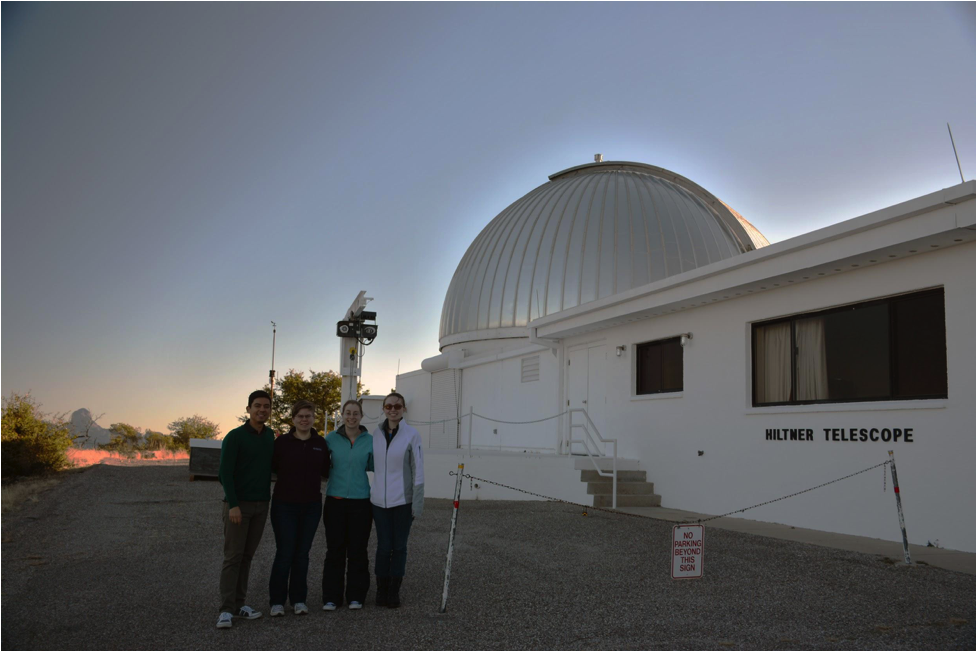

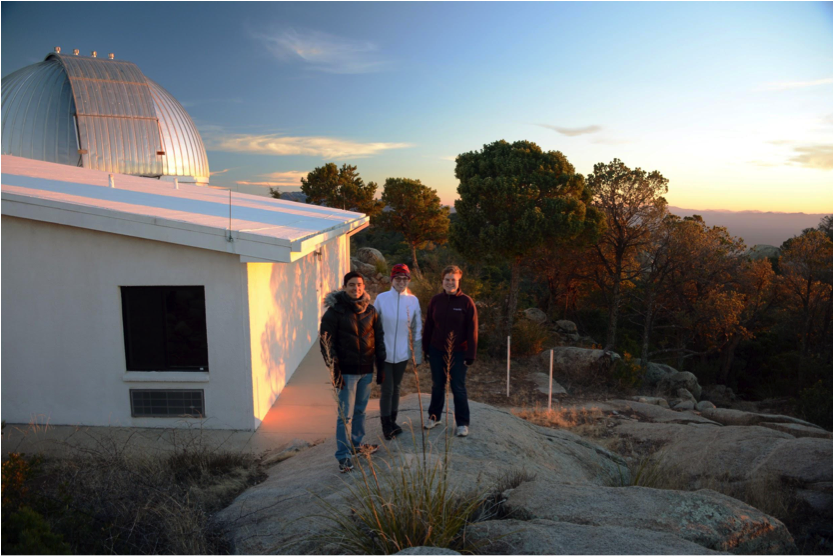

Ellie Schwab and Victoria DiTomasso, two CUNY Macaulay Honors College and AstroCOM NYC students, joined in our January/February run. Both have participated in remote observing with IRTF and Keck, but being at the telescope is an irreplaceable experience. Here we are behind the 2.4m (our telescope, with the silver dome), watching the sun set over the 1.3m down the hill.

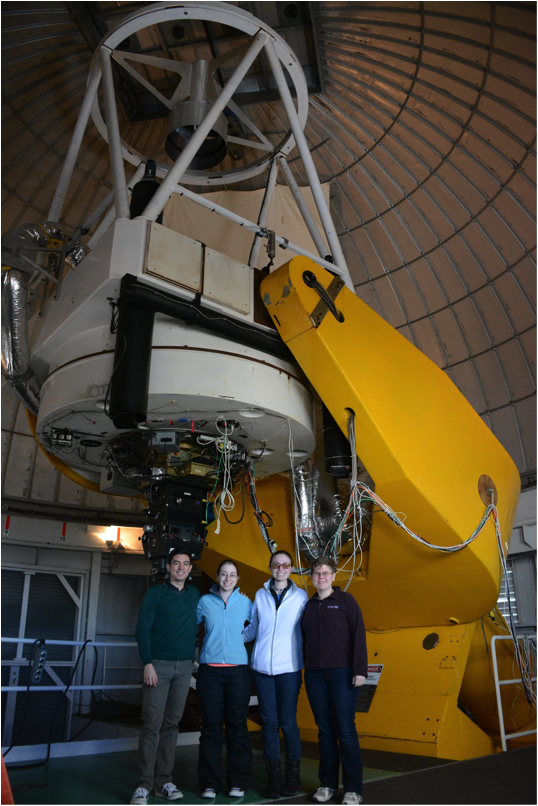

After the sun goes down, we head back to the dome to open up the telescope and get ready to observe. We didn’t have any critical targets early in the night, so we took our time on this run and didn’t do much during twilight. Here we all are inside the dome while it’s still bright out. We’re in front of our telescope, which has all the instruments attached beneath the mirror.

Once twilight falls, the real work begins. The first night is always a little slow, even for experienced observers, as we reacquaint ourselves with the telescope and instruments. Alejandro and I did most of the work for half the night, then we started showing Ellie and Victoria what to do. They were quick learners – by the second night, they were mostly running the show!

After two nights, Ellie had to head back to NYC – and (thankfully for her flight back) she just missed the winter storm that kept us locked down for the next two nights. It was by far the worst storm I’ve seen in five runs at MDM; rain, ice, and snow, plus winds from the West that gusted to over 50 mph! As you can see in the picture above, the shutter on the 2.4m dome faces Northwest, and it was blasted with precipitation all night long. When the staff rotated it around the next morning, here’s what we saw:

No getting that open! The sky was overcast, and the temperature never got above freezing, meaning the staff couldn’t thaw the dome for us. So we knew as soon as we woke up that the next night would be a wash — although the clouds stuck around too.

Thankfully, it warmed up enough on the following day to thaw the dome, and the clouds saw fit to move on, so we could start observing again on our fifth night.

Victoria, Alejandro, and I rotated through tasks, with one person in charge of sending the telescope to its new coordinates and setting up the exposure, one person setting up precise pointing and guiding at the new position, and one person rotating the instrument to account for our sky position.

On the sixth and last night, Alejandro headed to bed early so that he could drive us down to the airport in the morning, while Victoria and I stayed up to finish the observations. In previous runs, I’ve been alone during the last half night, but it was nice to have some company! After a couple of hours of sleep, we piled into the car and started our trek back to NYC.

It was great to have Ellie and Victoria on this run (and not just because extra hands mean less work for us!). Remote and queue observing strategies are becoming more popular, and do have a lot of funding and environmental benefits — there’s no way BDNYC could have our big IRTF observing parties if we had to go to the telescope. However, they also distance astronomers from the instruments and people collecting their data. It’s important for students to experience observing hands-on if possible. I’m glad our access to MDM at Columbia could provide this opportunity for Ellie and Victoria to poke around the telescope and get a more hands-on experience with observing.

From Ellie:

It was wonderful to have my first observing run on MDM’s 2.4 meter optical telescope with great company, my fellow observers: Stephanie, Alejandro and Victoria. Not only did Victoria and I get to co-run the telescope almost entirely ourselves for a full night, but I also got to experience the entire observing process first hand. I learnt how to cool the telescope’s detector with liquid nitrogen, monitor the airbag stability, rotate the instrument, send coordinates, locate the star, train the guider and throughout it all I still got to peek outside and peer up at the beautiful milky way and the five planets that were in alignment.

While the sun was still up, we all had the chance to travel up the mountain to Kitt Peak and see the WIYN telescope up close. It was fascinating to look at the principal mirror and see the system of fiber optic spectroscopy in place in the basement and to wander around the mountaintop, soaking in the sun and the views. I feel so lucky for this chance to travel to MDM – it was thoroughly enjoyable and a great learning experience!

From Victoria:

Going into it, I did not expect my six nights at MDM to be like my daily life as an undergrad at Hunter College. I had anticipated some of the obvious differences; adapting to a nocturnal sleep schedule, seeing a mountain landscape from my window as opposed to a brick wall, and experiencing actual darkness at night.

What I had not foreseen was the distinctive pace and priorities that we adopted while observing. My life as a student, especially in the fast paced city of New York, has been characterized by a “go, go, go” attitude. The number one prerogative is always to get the job done, with bonus points for doing it as quickly as possible. It surprised me that while observing, when time is quantifiably valuable, we prioritized the health of the telescope over our goal of getting data. I learned to heed warning signs as opposed to charging past them. We made sure to keep our eye on wind and weather conditions, and we paid attention if anything seemed to act up. For example, a few hours into our first night, we noticed that the star we were observing suddenly jumped in the view of the telescope. Instead of carrying on once the jumping ceased, we investigated the problem, finding that it was caused by a malfunction in the airbags that support the telescope.

If such a hiccup had occurred in my everyday life, if my computer suffered a momentary glitch, for instance, I would simply push past it. This shift in priorities served as a constant reminder of the value of the equipment we were working with. That 2.4-meter telescope can help us unlock the secrets of the universe; it is certainly worth respecting the limits of its ability to function in poor weather. Beyond that, I found myself slowing down and taking care in everything I did. This change of pace gave me the time to appreciate how extraordinary it was to be there and how lucky I was to have been able to live, learn and work at an observatory.